I want to write something for my students about this, or at least prepare something to say to my students about this, so I’ve decided I need to first write about it for myself to start sorting out my thoughts and ideas.

How do we write about issues in a world that is so terribly divided on every single point?

On Saturday, I heard that Justice Scalia was dead, and about five minutes later I heard that key Republicans had already announced that they would attempt to block any attempt President Obama might make to nominate a new Supreme Court justice. There was no waiting period before politics took over. There was no social contract that said we defer debate for a certain amount of time out of respect for the deceased and for his family. We went straight from the news of the loss to posturing about how we are going to use this to thwart each other politically.

This is not what I call normal. It is not what I call functional. Yet this is now our reality. This is what politics in 2016 looks like.

Back in my own day as a student writer, I was taught Rogerian argument in which the goal is not to shut down the other person but to open up dialogue so as to work toward consensus or compromise or workable solutions or at least a multi-sided understanding of the issues at stake. In this method, you don’t have to agree with the opposing side, but you do have to show that you respect and understand the other side.

Respect and attempts to understand seem to have left the building of American politics. What passes for political debate these days is so polarized that it seems risky to me to even attempt to discuss anything that really matters in the classroom. But if we don’t discuss things that matter, why are we even there?

The risk stems from the constant demonizing of the other. Label yourself as liberal, and half the country thinks you are evil. Label yourself as conservative, and the other half thinks you are evil.

It seems to me that a thinking person should make judgments issue by issue after careful analysis of the facts, not based on liberal vs. conservative catch phrases or a desperate attempt to avoid being associated with “the other side.”

So how do we get past this? How do we discuss issues in a meaningful way?

One thing that comes to mind is Jonathan Haidt’s work on liberal vs. conservative thinking.

I read his book The Righteous Mind, and I found it very thought-provoking. If we are going to have meaningful discussion, we have to first get beyond the idea that people who disagree with us are bad or stupid or uncaring or dishonorable. They are none of those things. They simply think differently. Some people think differently because they bring a different set of life experiences to the table, and others think differently because their brains are just wired to prioritize information in a different order.

We were all so divided over the Syrian refugee crisis, for example. In this case, we had two main motivating factors that determined where we stood on the issue of whether or not to allow Syrian refugees into the United States in the wake of the attack in Paris: (1) concern for harm being done to others; (2) concern for threats to ourselves and to those we love.

Both ways of seeing the problem are real. Both ways of seeing the problem are legitimate and based on real facts. Both are based on values.

Yet we were incapable of coming to consensus because some people’s brains are wired to prioritize around a core motivation of compassion, and some people’s brains are wired to prioritize around a core motivation of protection.

The end result of this in our current political climate is that a bunch of otherwise rational, kind, informed, and well-meaning people completely demonized one another over a very honest disagreement.

This realization doesn’t solve all of our problems, but it gives us a place to start having better discussions. If we want to talk about or write about issues, then, we have to start with a few guiding principles:

- Don’t assume people on the other side are bad people.

- Don’t assume people on the other side are lacking in intelligence.

- Don’t assume people on the other side have an inferior understanding of the facts.

- Don’t assume people on the other side are lacking in morality.

- Don’t assume people on the other side want to see harm come to you.

- Don’t assume that differences in opinions are dangerous to you.

It is okay for people to be different. It is okay for people to look at the same information and come to different conclusions.

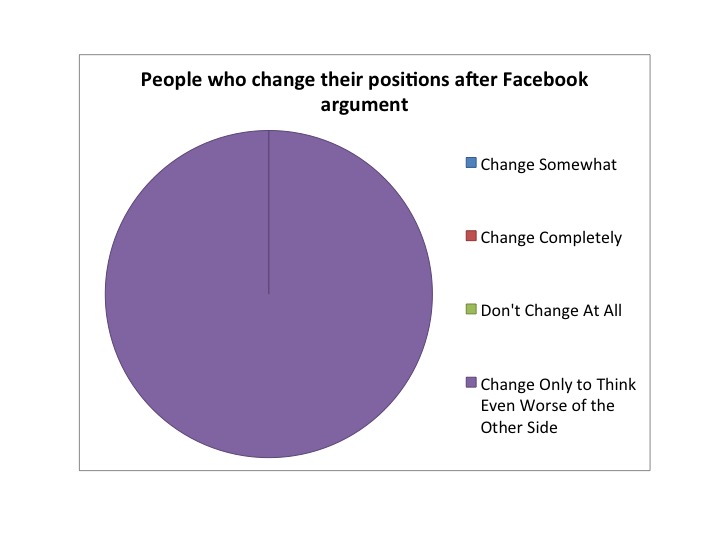

Once we agree that disagreement is okay, we can understand the most universal truth of polarized arguments, which is that you aren’t ever going to win over people who don’t think the same way you think by telling them what you think.

Thus, we can add one more don’t.

- Don’t assume you can beat a person on the other side of an issue into submission with the steady hammer blows of your facts. If everyone saw the facts the same way you see them, there wouldn’t be an argument.

I suppose then my own conclusions are that we don’t need lessons in argument so much as we need lessons in listening, lessons in respect, lessons in not jumping to conclusions about other people, lessons in considering other perspectives as valid.

I suppose then my own conclusions are that we don’t need lessons in argument so much as we need lessons in listening, lessons in respect, lessons in not jumping to conclusions about other people, lessons in considering other perspectives as valid.

Good luck on that, right?

Maybe we can’t all make friends and make nice. Maybe even basic respect for one another is just a pipe dream. If that’s the case, though, I’m reminded of something I learned from Ender’s Game–The only way to defeat the enemy is to know the enemy. The only way to know the enemy is to love the enemy.

In the moment when I truly understand my enemy, understand him well enough to defeat him, then in that very moment I also love him. I think it’s impossible to really understand somebody, what they want, what they believe, and not love them the way they love themselves. And then, in that very moment when I love them…. I destroy them.

Orson Scott Card, Ender’s Game

Yeah, that’s creepy. I think I might be giving up now.

Can’t we all just get along?